Node 20 - Experimental

Ended

October - December 2024

Countries: Albania

Nodes: Tirana

Beyond Irregular Pathways: Cultural Frameworks, Solidarity Networks, and Agency in Albanian Migration to the UK

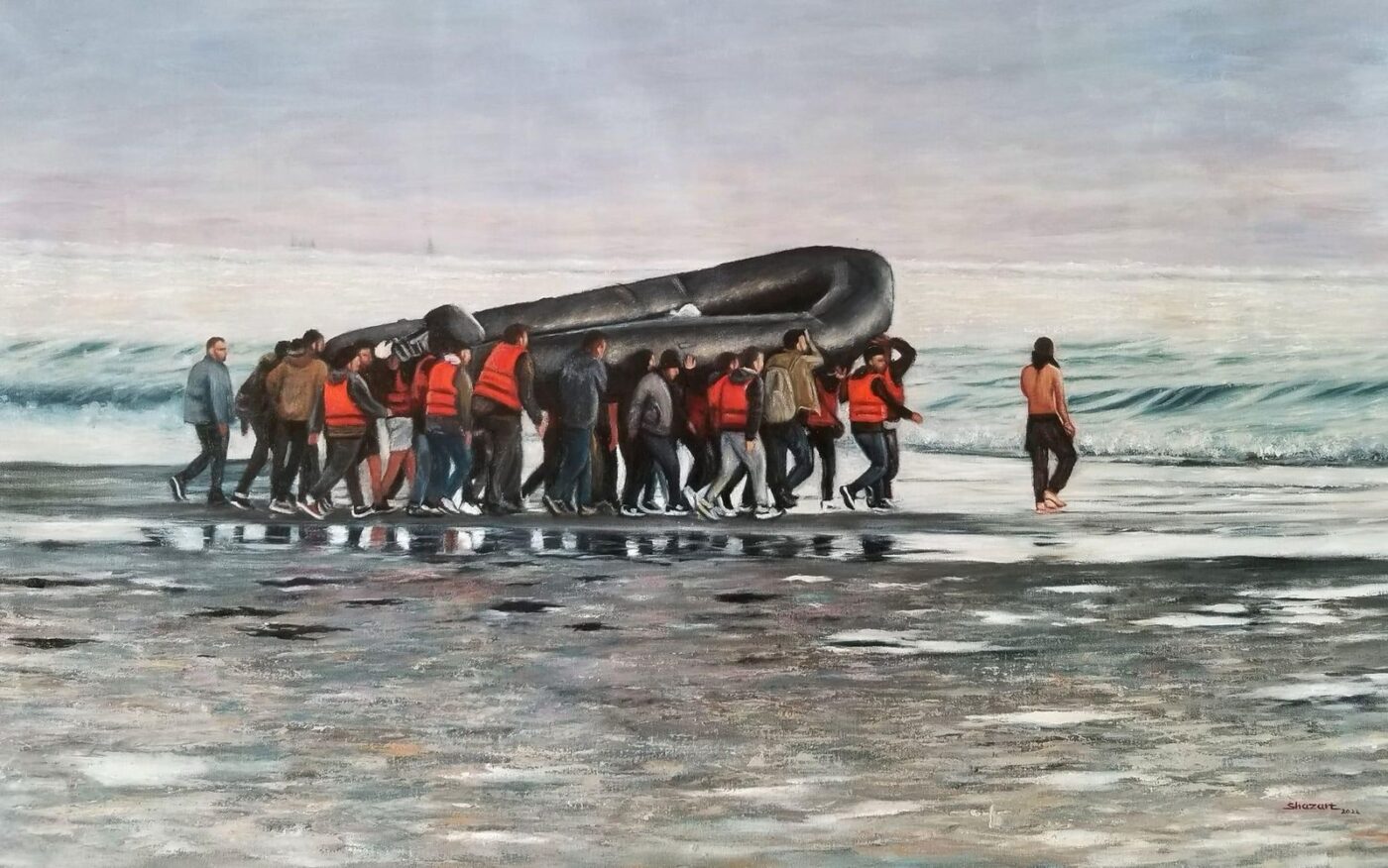

This node report examines Albanian irregular migration to the United Kingdom through a socio-cultural lens, challenging dominant narratives that frame irregular migration primarily within narratives of criminality and trafficking.

Drawing on fieldwork with Albanian migrants, the research explores how traditional cultural constructs—Kurbet (temporary labour migration), Kanun (customary law), and Besa (moral code of trust)—shape contemporary mobility practices and solidarity networks. Through digital ethnographic methodologies, including participatory storytelling workshops and co-created podcasts, the study foregrounds migrants’ voices and agency while documenting the complex interplay between cultural continuity and adaptation in contemporary migration contexts.

The findings highlight how these cultural frameworks simultaneously provide moral grounding and undergo a transformation in response to modern migration challenges, particularly the commodification of migration routes. By examining the multifaceted experiences of Albanian migrants navigating perilous journeys to the UK, this research contributes to broader scholarly debates on the intersections between tradition, agency, and structural constraints in migration studies, offering nuanced insights into how cultural traditions inform contemporary practices of mobility and solidarity.

Generative Narrative Workshop: Co-creating Migration Stories

The two GNW podcasts—”Journeys of Hope” (Udhëtime Shprese) and “Albanian Solidarity in Migration Journeys” (Solidariteti Shqiptar në Udhëtimet e Migracionit)—serve as platforms for sharing migration stories while connecting individual experiences to broader cultural and societal structures. These podcasts function as ethnographic documentation that captures the lived realities of Albanian migrants through their own voices and perspectives. As one participant reflected:

Sharing my story through the podcast allowed me to connect my personal journey with those of others. It wasn’t just about telling what happened to me, but about understanding how my experience fits into a larger pattern of Albanian migration.

The podcasts incorporate traditional cultural frameworks like Kurbet, Kanun, and Besa, examining how these concepts shape migration experiences and solidarity networks. This approach enables a deeper understanding of the cultural dimensions of migration while providing participants with a platform to articulate their experiences in ways that resonate with their cultural heritage.

Journeys of Hope: Exploring Migration and Solidarity Networks Link

Albanian Solidarity in Migration Journeys: Narratives of a Living Heritage. Link